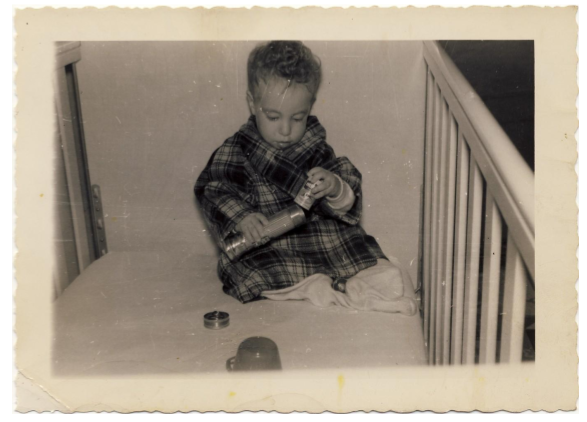

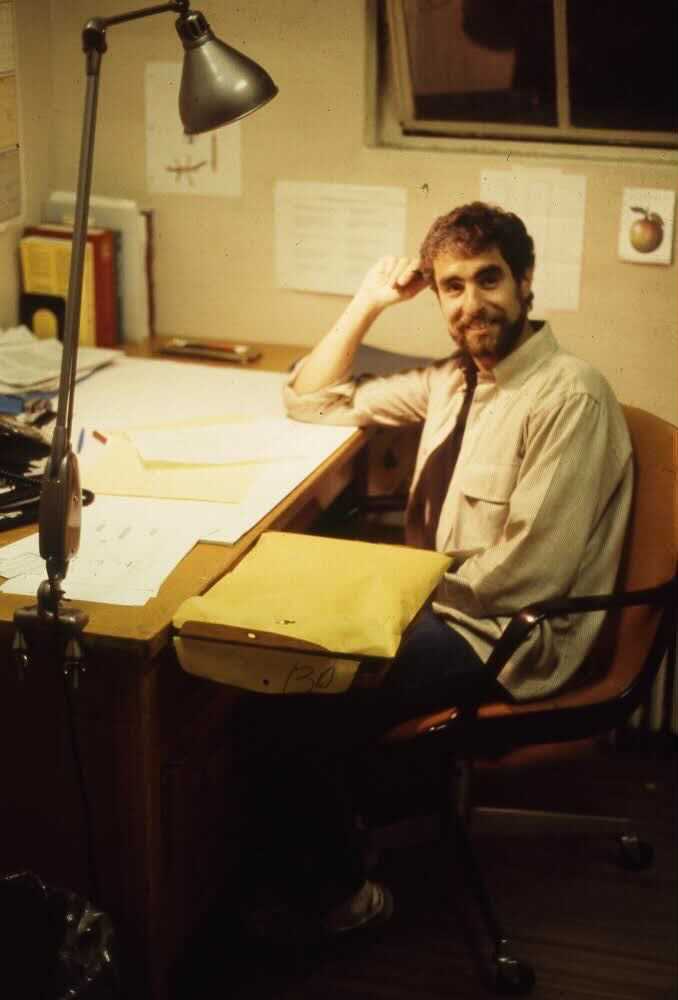

As a child growing up in New York, Bill had no idea what he wanted to be. He always liked to tinker with things, taking them apart and putting them back together to see how they worked. His father was a high school English teacher, and Bill enjoyed reading a lot, so he initially considered a literary career or a career in the humanities. However, he was drawn to science after trying drugs in high school: “I wasn't a big druggie, but I graduated from high school in 1969, so to put that in perspective, we were kind of the avant garde of the drug use groups, and by the time I left high school, everybody was getting high all the time,” he clarifies. This experience made him curious about the brain. “So I did a little drug experimentation and I thought, ‘Wow, this is just unbelievable,’” he adds, “If you could take small amounts of some chemical and it could have such profound effects on your perception and your consciousness, then maybe chemistry could unlock the secrets of the brain.” Bill also enjoyed chemistry in high school and was thus drawn to studying the chemistry of the brain.

Upon arriving at Reed College in 1969, Bill was unsure of what path he should take to pursue this budding curiosity because the field of neuroscience was so new: the first meeting of the Society for Neuroscience was in 1971, and neuroscience wasn’t offered as a college major. Initially, he decided to pursue his original interest and major in chemistry: “I was good at chemistry and really liked chemistry, so I figured I could maybe learn enough chemistry to figure out the brain,” he explains, “But the problem with being a chemistry major was that I never learned anything about the brain.” Unsatisfied, he switched his major to psychology and combined it with classes in biology to try to learn more about the workings of the brain.

At the end of his time as an undergraduate, Bill again wasn’t sure what his next steps should be. He wanted to continue to study the brain but didn’t really have mentors to point him in the right direction. He had enjoyed doing research as an undergraduate, but also considered becoming a medical doctor. He thus applied to both PhD and MD programs, and decided to go to medical school. “I wasn’t super excited about being a doctor,” he says, “But I thought if I go to medical school, I can study the brain and figure the rest out later. It was kind of a placeholder, in a way.” In medical school, he fell in love with studying the brain again. He tried to do research as a medical student but had a terrible experience, so instead he decided to train as a neurologist.

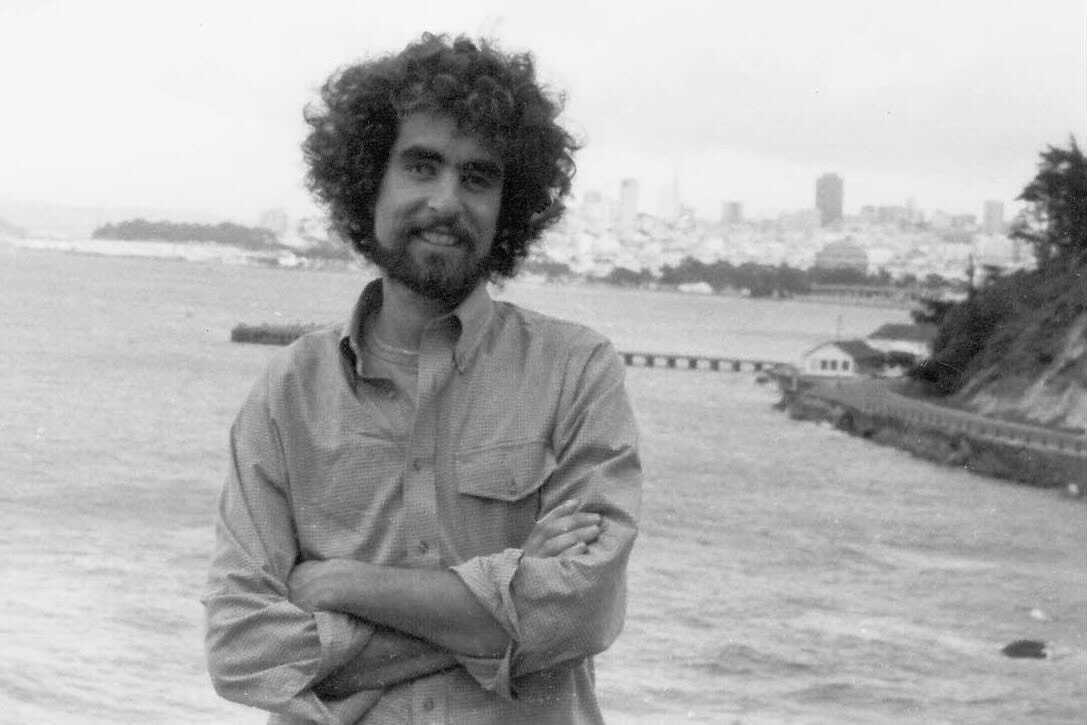

After finishing his neurology training in Boston, Bill decided he wanted to give research another shot and thus applied for postdoctoral research positions. This transition was difficult. He was rejected many times, and was told that he couldn’t go into research as a medical doctor. In spite of these struggles, he was eventually offered a postdoctoral position in medical imaging at Lawrence Berkeley National Lab (LBNL). This position was especially opportune for Bill because his girlfriend at the time wanted to move to California, so he accepted the position and moved across the country to Berkeley. Despite being teased by other researchers for being an MD, he loved his experience at LBNL, where he learned neuroimaging techniques like positron emission tomography (PET), the same method his lab uses today. At the time, before functional MRI imaging, someone interested in functional human neuroimaging would use either PET imaging or electroencephalography (EEG), a method of recording electrical brain activity. Bill’s interest in neurochemistry drew him to PET imaging. When he came to California, he met another neurologist-turned-researcher who chose the other path pursuing EEG work and who would later become his colleague at Berkeley, Bob Knight.

Bill joined the faculty at the UC Davis School of Medicine after finishing his postdoc. As he became more involved with research, he started seeing patients less often, and he realized that he was much more passionate about research. Research fit his personality and interests better; he had always been drawn to asking questions about how things work and figuring things out. “I wish I could say I had a driving urge to answer a fundamental question, but that’s not true,” he adds, “I just really liked the process of research. I liked the feeling, and if you really like research, I think you can find any number of projects that could attract you.” Additionally, his work on PET imaging and as a neurologist had both exposed him to studying and treating Alzheimer’s disease. Because there are no effective treatments for Alzheimer’s, Bill also felt he could have a bigger impact as a scientist and researcher than as a neurologist. “I just felt like I wasn't really helping people enough as a neurologist. If you can take out tumors and can save someone's life it's probably a lot more satisfying than what I was doing,” he says, “But when you’re taking care of people with Alzheimer's disease, you’re fairly limited in what you can do.”

He thus left medicine for a full-time teaching and research position as a Professor at UC Berkeley, where he now leads his own lab and works with the same LBNL facilities he used as a postdoc. One of the focuses of his current research is PET imaging, which uses radioactive tracers to visualize various physiological processes implicated in Alzheimer’s Disease. Bill remarks that this focus on radiochemistry brings him back to his initial curiosities about neurochemistry that drew him to the brain: “The one thing that's kind of interesting about how it all worked out is a lot of the stuff that I do with PET now is fundamentally chemistry, which comes full circle to what got me motivated in this field. I tell this story a lot, and it seems like I just made it up,” he says, “because it's so strangely circular, but it's absolutely, totally true. It didn’t happen by planning; it really happened very accidentally.”

Bill attributes a lot of his path to luck. “A lot of successful people in America are pretty self centered and believe they did it all by themselves,” he says, “but my story is so clearly not that. I worked hard and all, but so much of it was just luck.” One of the good fortunes he notes of his career is that he “hit the zeitgeist” in his field at its peak twice: once in the early 1980s and a second time in the early 2000s. In the 80s, Bill started his career as a researcher using PET imaging just as PET was getting going. Then in the early 2000s, while he was a professor, the molecular basis of Alzheimer’s became better understood and PET ligands were developed to image Alzheimer’s pathology. PET imaging took off again, this time to study the aging brain, which is a key focus of Bill’s research. “I happened to be in the right place at the right time twice in my career, and you’re fortunate if you can get there once,” he explains, “I think that's a lot of who gets hired for jobs and who ends up where. You can move a field forward by your discoveries, or you end up in a field that's moving forward. I think for me it was a little of both, but more the latter, to be honest.”

Despite growing up in New York and attending medical school and residency on the East Coast, Bill likes living on the West Coast, where he’s stayed since his postdoc at Berkeley. He finds things a little more relaxed here, and also enjoys spending time outdoors in California. He met his wife, Robyn, in California, and enjoys a lot of outdoor activities, especially riding his bike. Before the pandemic, he commuted 6 miles each way to and from work by bike. Now, despite not commuting, he enjoys having a little more flexibility in his schedule to bike whenever he wants to. One of the reasons Bill enjoys riding his bike so much is because he likes to cook and to eat. Bill finds these hobbies very complimentary: “There’s this tension that the more I eat, the more I have to ride my bike,” he says with a laugh, “So I get to stay in shape and enjoy cooking, too.”