Marla grew up in a working class family in Ventura County, Southern California. “I knew no scientists,” she says, “I think when I was growing up, I didn’t even know what scientists were.” She attributes this to the lack of female scientist role models in popular culture. On top of that, the quality of education and the science classes at Marla’s high school left much to be desired. Only around 10% of the students went to college, making it difficult for Marla to picture herself as a professional, college-educated woman. But one year, the physics teacher took a leave and the class was taught by a graduate student from the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). Marla so thoroughly enjoyed this class that it motivated her to apply to and attend UCLA.

Upon arriving at UCLA, Marla met with the intake officer of the School of Engineering, who told her that she did not have the background to succeed in engineering and that she was going to fail. Marla believed the officer, but also did not want to fail. She therefore took many classes outside of engineering, and switched majors about four times in two years. After two years at UCLA, Marla transferred to UC Berkeley. “It was because I had a boyfriend at Berkeley and Berkeley was far away from my childhood home. So, you know, all the wrong reasons”, she explains.

Marla had a choice of two majors at Berkeley if she wanted to graduate in four years: economics and physics. Since the Department of Economics did not take transfer students, she majored in physics. Marla was very successful as an undergraduate. She did an honors thesis and earned the Department award, given to the best undergraduate student in physics. A TA recognized her potential and encouraged her to apply to graduate school. “I still had no idea what graduate school was at this point”, she says, “I thought graduate students were professors and professors were Gods or something, and I just really didn’t understand how the whole thing worked”. Nonetheless, with the help of the same TA, Marla prepared her graduate school application and joined the Physics PhD Program at UC Berkeley.

During her time at Berkeley, Marla started the women’s Ultimate Frisbee team and did her graduate work in experimental solid state physics. “In physics”, she says, “you spend all your effort doing experiments that will produce data points that fall on a curve you already know”. While this was very satisfying, Marla was unsure whether she wanted to do physics research for the rest of her life. This uncertainty was compounded by her graduation year: 1991. The Soviet Union had just collapsed, and along with it went the U.S. Defense Industry, which employed most physics PhDs. Marla applied for several positions in science policy but was rejected from all of them. She eventually found a good fit for her postdoctoral work in David Tank’s group at AT&T’s Bell Laboratories, which combined neuroscience and physics, and Marla took on a project imaging calcium influx to retinal ganglion cell axon terminals in the frog tectum.

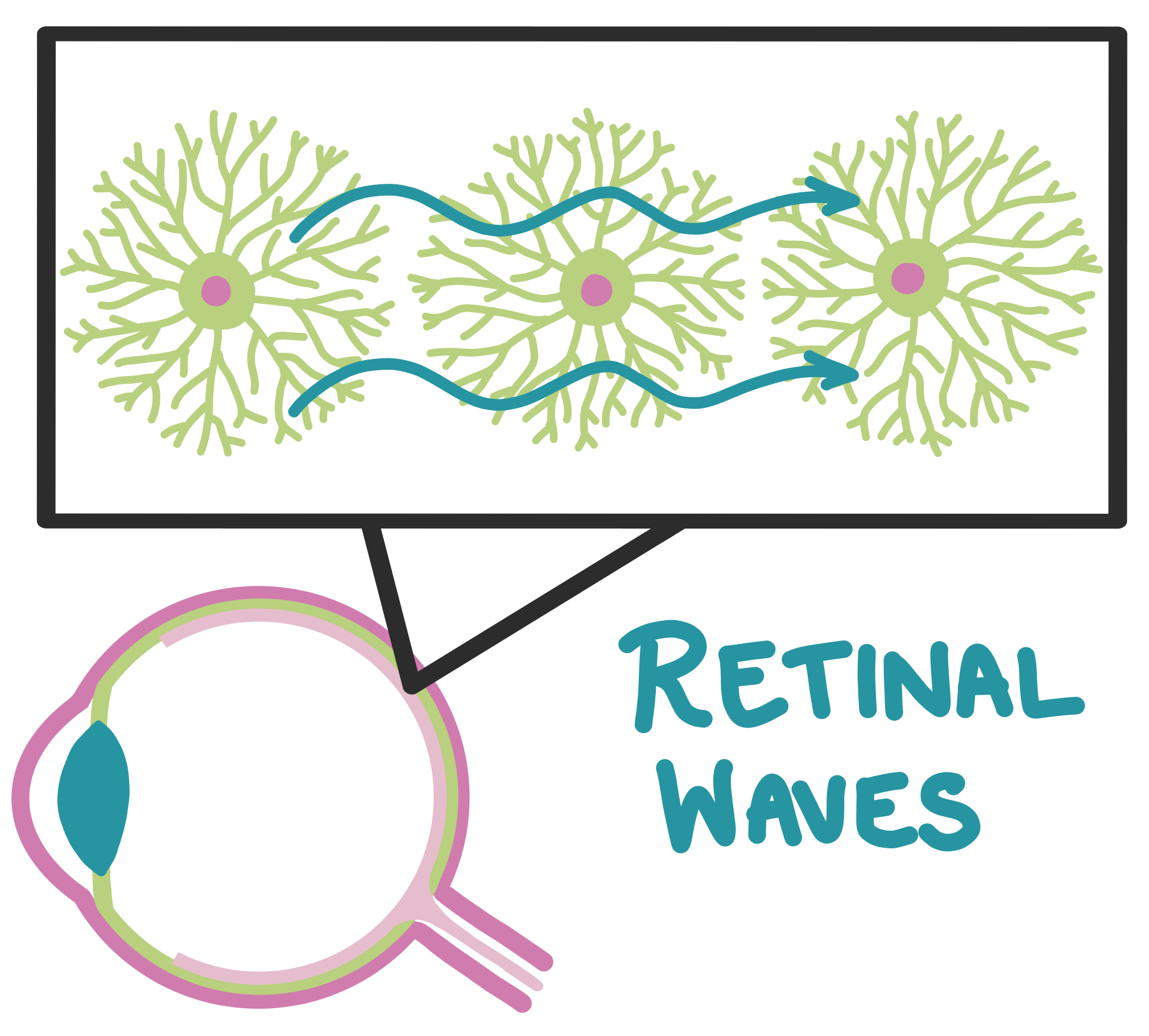

Marla had a lot to learn as a postdoc. “I probably didn’t even know what a cell was when I finished my PhD,” she says. After attending a summer neurobiology course at the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, MA, and two years working at Bell Labs, she decided to continue to pursue this interest in neurobiology by doing a second postdoc. She felt increasingly drawn to biology. “Biology is exciting because you can discover something new every day, but the downside is that you can never know if you’re right”, she explains. Eventually, Marla contacted Carla Shatz at UC Berkeley, famous for being the first woman to earn a neurobiology PhD from Harvard and for holding the prestigious position of the President of the Society for Neuroscience. “I had no idea who she was”, Marla says, “but I met with her and we had this great idea to do calcium imaging in the developing retina, a line of research her lab had just initiated.” It was during this second postdoc that Marla recorded her first retinal waves. Retinal waves are spontaneous firing patterns that drive the development of neural circuits necessary for vision, and remain a key focus in her lab today.

After successfully completing her second postdoc at Berkeley, Marla accepted her first position as a tenure-track principal investigator (PI) at the National Institutes of Health (NIH). She was pretty happy about this, because she had always wanted a job with high income stability. “My parents got divorced when I was very young; we were very poor, and we were on food stamps for a while. I swore that was never going to happen to me as an adult,” she says, “when I learned about tenure, I liked that.” At the same time Marla’s husband, Dan, was a postdoc at the NIH. After he finished his postdoc, they were recruited to UCSD together, where they established their respective labs and received tenure. Marla was happy at UCSD, but missed her life and friends in the Bay Area. After 7 years, Marla and Dan were offered faculty positions at UC Berkeley. Marla and Dan have now been at UC Berkeley for 13 years, both running successful labs and raising a now adult son.

Marla speaks very openly about her struggles with impostor syndrome throughout her scientific career (watch her talk about it here). There were very few other women scientists around her, especially when she was in physics. “I always felt like I didn’t belong, but I never wanted to quit. I just assumed I would get fired. When you come from a working class family, getting fired is just something that happens all the time, and you move on”, she explains. Marla encourages trainees who struggle with impostor syndrome to not take themselves out of the game. Almost everyone is confronted with impostor syndrome more than once in their careers, even tenured faculty members. “There’s someone that’s better than you for any given area, but there’s only one of you. Don’t let the criticisms, failures and things you don’t understand get to you. Learn from it and move on”, she says, although she acknowledges that is much easier said than done.

Outside of work, Marla likes to go hiking, running and is a bit of a Cal sports fan. “Actually”, she says, “I don’t run, I plod.” She also enjoys reading and is part of a book club. In keeping with her interest in science policy, she is a political news junkie and volunteers for political campaigns, as she believes it is crucial that politicians at every level should care about science and integrate it into their policies and decision-making process. She also desperately wants to see more women in political leadership positions and hopes that in her lifetime a woman will be elected as President of the United States.